Fancy Cancels

by John Hillson, FRPSL, FCPS

Intaglio (Recessed) "X" Cancel |

IntroductionAn interesting period in Canadian postal history is the approximately quarter of a century following Confederation (1867), when the use of Fancy Cancels, sometimes referred to, perhaps a little condescendingly, as corks, was in its heyday. This article explains what they were, how they were used, what to look out for, and how to collect them. |

What were the cancelling devices made of?

The generic use of the term "corks" is something of a misnomer, and the suggestion that these cancelling devices were made from the stoppers of bottles “from which the spirits had fled” is also somewhat misleading, and possibly a slander on the abstemious postmasters of the new Dominion. The fact is, there were commercial enterprises advertising to postal officials, both in Canada and across the border in the United States, sheets of cork for sale for use in the manufacture of home made cancelling devices. It is equally true that there were also other commercial enterprises offering to sell ready made cancelling devices to these same group of people.

So, while there is no doubt that many of the home made cancelling devices used were made by postmasters from cork, equally devices used could be from rubber, wood, metal, or even from what came readily to hand.

Why did postal workers make their own cancelling devices?

Why was it necessary for these post office workers to do their own thing in the first place? There were three interconnecting reasons. First, the postal regulations of the time, second, the rapid expansion of postal services and the opening of new post offices to service that expansion, and third, the inability of the Post Office Department to supply killers needed to meet the requirements of the regulations because of that rapid expansion. Why did the heyday last about twenty-five years – or thereabouts? Because in 1894 the postal regulations that had a direct bearing on the cancellation of postage stamps changed.

and the placement of the postmark according to regulations.

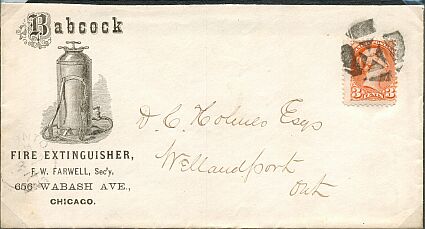

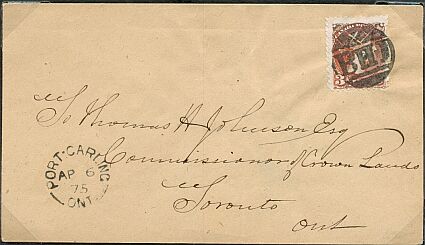

Postal Regulations

The regulations concerning the postmarking of envelopes at the time of Confederation may be summarised as follows: The item was to be postmarked in the lower left corner with the date and name of the forwarding office; if the office had not been issued with a suitable date stamp it was to be done in manuscript. Adhesive postage stamps were to be obliterated with a killer, not the date stamp. If no such killer had been issued to the office, the postage stamp was to be cancelled with a pen and ink cross, or by a suitable killer provided by the postmaster. The office of destination had to record its arrival with its date stamp, or in manuscript.

The reason postage stamps were not to be cancelled using a date stamp is that if it were the only postal marking on the front of the cover, and the adhesive stamp was removed, the record of the item’s time in transit was lost. This could leave the Postal Authorities open to a charge of undue delay, which they wanted to avoid.

What makes a fancy cancel fancy?

Ottawa Crown Cancel |

A question sometimes posed is: “What constitutes a fancy cancel?” Should it be confined to homers (home made devices), or to only official postmarks, such as the Ottawa Crown? |

" 6" rate marker misused as a cancel |

Or the misuse of devices such as rate markers? |

Cancel made from a brass seal |

Or the brass seals used to secure mailbags? |

Or straight line markings which clearly could not have been whittled out of cork or wood?

My own view is “why not?” - but, like all things, what one decides to collect, or include in a collection is entirely a matter of personal choice.

Fakes

| The downside of collecting fancy cancels is the simple fact that even when quite scarce items could be picked up for a song "almost" fakers found it profitable to "improve" otherwise uninteresting items. Indeed the most prolifically faked cancel is the aforementioned Ottawa Crown. Curiously, such are the peculiarities of collectors that the fakes seem to command more or less the same prices as the genuine. In fact, it surprises me that, since the points to look for in determining whether or not an Ottawa Crown is genuine are well documented, so many collectors specialising in fancy cancels are still caught out. | Masonic Emblem

|

|

Fake Indian Ink Cancel |

Genuine |

|

As far as the generality are concerned, points to look out for are first, has the stamp evidence of another postmark underneath the fancy cancel? If so, be suspicious. Second, does the ink look right? Indian ink was not used in post offices to cancel stamps. Third, if it does, is it ink or watercolour? To test it is probably unwise to immerse the item in a bowl of water unless one actually owns it; if one does not it might be a bit tricky dealing with the vendor. Moisten the tip of one’s little finger and gently rub over a small part of the cancel. If it starts to fade, return it to the owner with the suggestion that he/she immerses it in water for a while. Particularly if it is a cover!

Do not be over worried if you do occasionally buy an item that turns out to be dodgy, it is part of the learning process and the cost may be regarded as part of the fee!

Organizing your collection

Fancy cancels made by postal officials fall into several groups. The most prolific are simply cross cuts on a generally round background which were most likely made from cork and which includes cogwheels, sunbursts and arrowheads.

Letter Cancel (Kentville) |

Monogram "YK" (St. Francis du Lac) |

Next are letters, monograms and town names. |

Intaglio Monogram (West Arichat) The letters, "EM" stood for the Postmaster Emil Mouchet |

Third are leaves, particularly maple leaves, which is not surprising, and plants.

| Fourth, crowns, stars, crosses and similar devices such as masonic insignia, anchors and the like. |

Star Cancel (Hawksville) |

Maltese Cross (Sherrington) |

Number Cancel (Toronto) |

Number Cancel (Port Hope) |

Date (1881) |

Fifth, numbers and years. |

Bogey Face Cancel (Montréal) |

Sixth, miscellaneous items such as the curious Nicaragua Arms cancel used by the St. Genevieve de Batiscan, bogey faces and the like. |

Bogey Face Cancel |

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed this brief introduction to yet another fascinating aspect of philately.